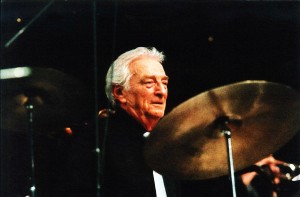

Tony Kinsey is without question one of the most influential and important personalities in British post-war modern jazz. He may not be as flamboyant and extrovert as some of his contemporaries, but his quiet and shrewd professionalism as a bandleader, and his understated but peerless style as a drummer, ensured that he performed and recorded continuously and successfully through what was perhaps the most prolific era of the genre during the ‘50s and early ‘60s.

Alongside names like John Dankworth, Ronnie Scott and Tubby Hayes, Tony is one of the fulcrums around which the British modern jazz scene revolved, and his constantly evolving trio, quartet and quintet line-ups during the period when he held down legendarily long residencies at Studio 51, and then most notably The Flamingo, saw a veritable who’s who of British jazz luminaries pass through the ranks of his ensembles.

Born in Sutton Coldfield, h e learnt drums from the age of seven, and in the late ‘40s got his first professional engagement at The Blue Lagoon Ballroom in Newquay where members of the band were paid £10 a week – a pretty good wage in the immediate post-war years. After a while the resident pianist moved to a gig in another hotel. Tony recommended Ronnie Ball, whom he did not know personally – he had heard him at the Casino Ballroom in Birmingham and thought he was really excellent, so got his details and recommended him to the band leader, Jackson Cox.

They soon became very close friends, and in 1948 they moved to London – they had a double wedding a couple of years later. Tony found work in some of the capital’s ritzier night-clubs, but, hating the music he had to play, got a job with Ivor Noon’s band on the Queen Mary on the New York run – part of what was generally known in the business as “Geraldo’s Navy”. Along with many British jazzmen of the era, Tony took the work on the transatlantic liners in order to visit the jazz clubs in New York and see the great bebop stars like Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Buddy Rich, Kenny Clarke etc.. While there, Tony also studied percussion with Cozy Cole and Bill West. Tony’s own recollection is that he made about seventeen trips on the Queen Mary.

In 1950, he joined another bandleader who was to become one of the key personalities of British jazz, when he became a founder member of the John Dankworth Seven, but, tiring of the endless touring, left after two years to join Ronnie Ball’s Trio at the 51 Club (named after the year of its opening) in Great Newport Street. Ronnie left to go to the USA – Tony was meant to follow him but decided against it, and instead took over leadership of the trio, playing with pianist Dill Jones and bassist Stan Wasser. As he modestly observes, he “became a bandleader by chance”.

He was also, even at this early stage, making his mark working with visiting American stars – a high-profile role he would fulfil several times during the next few years. In 1952, Lena Horne was opening at the London Palladium, and for some reason, Billy Clarke, the drummer who had been accompanying her on her European tour, suddenly departed on the SS Liberty from Southampton. As the MM report says: “Clark, former percussionist with Duke Ellington and Mary Lou Williams, never opened at the London Palladium. Instead Lena substituted young British modernist Tony Kinsey. ‘He’s fine’ said Lena’s MD-husband Lennie Hayton.” The story was accompanied by a photo of Lena and Tony rehearsing. Playing alongside Arnold Ross, Lena’s regular pianist, and Joe Benjamin, Duke Ellington’s bass player, it was quite an experience and a considerable accolade, confirmed by an interview Lena did with Hit Parade magazine where she said: “Billy Clarke was replaced in Britain by Tony Kinsey and then by Jack Parnell- and your boys did as good a job as Billy!”

We went through the discography with Tony to get the background to all the various line-ups and sessions, but he made a point which comes out time and again in discussing this era with jazzmen, which is that the life was such a constant round of gigging and occasional recording, often with fluid line-ups of musicians, that it was hard to remember what happened at any particular session – it was just what you did for a living, and there was no particular grand plan at work. Asked, for example, to explain why the bass player changed for a particular batch of recordings, Tony generally said: “We probably just used X because Y wasn’t available”.

Tony also observes that hearing tracks that were recorded as singles or EPs several weeks or months apart as part of a collection was interesting – in one way, it was unsatisfactory in that the tracks tended to employ the same structure, which was in danger of becoming repetitive in an anthology context, while on the other, he recognised that “people’s playing changed all the time, and we never listened to our own recordings after they were done – there was often something we didn’t like, but they wouldn’t let us do it again, as the discs they cut them on were too expensive.” (The Esquire tracks were not made using tape – they were cut direct to master lacquers.) “We didn’t think of what were doing in any kind of special way – it was just what we were doing for a living.”

A scrapbook of press cuttings kept by Tony’s wife Pat provides an invaluable reference point, and the headlines from Melody Maker throughout the period of the recordings emphasise what an important figure Tony Kinsey had rapidly become in the jazz world (and also how effective a publicist Flamingo owner Jeff Kruger was).

In October 1953, Tony was featured on the front cover of Jazz Journal, and around this time entrepreneur Bix Curtis started his Jazz At The Prom concerts , and Tony’s trio were regularly featured, as well as at concerts like “Jazz For Moderns” at the Royal Albert Hall and Royal Festival Hall alongside the Ronnie Scott Orchestra and others. In February 1954, Tony and bassist Sammy Stokes accompanied Billie Holiday with her pianist Carl Drinkard as well as the band appearing on the supporting bill during her British tour. It was about this point that the Kinsey Quartet became resident band at Jeff Kruger’s new club The Flamingo, at the Mapleton Hotel, Leicester Square, attracted by an offer of significantly improved earnings from Kruger – £4 a night as opposed to 30/- (£1.50) at Studio 51. This gave the basis for a regular living for a working group, and for the best part of a decade this fairly high profile role in the heart of the capital’s jazz scene enabled Tony to cement an already substantial reputation.

Tommy Whittle moved on to form his own band in 1954, and the development that saw rapidly emerging star Joe Harriott join the Kinsey outfit was evidence not only of the high regard in which it was held, but Tony’s astuteness in spotting and attracting talented players. The other key addition was Bill le Sage coming in for pianist Dill Jones. Tony knew from his time with him in Dankworth’s band that Bill was not only a fine musician but a great organiser, and his influence in the musical direction alongside Tony reinforced the group’s highly professional approach.

In June 1954, the Quartet made a hugely successful appearance at the Paris Jazz Fair, leading to eventually unfulfilled rumours that they would be touring the USA – Tony commented that he would sometimes read stories about what he was about to do and think “Oh, am I?” Of the Paris gig, NME reviewer Mike Butcher wrote “Our own Tony Kinsey and his boys scored a great triumph, both with the French fans who cheered them to the echo, and with the musicians backstage. Tony’s drumming came as a revelation to many of the other percussionists present.”

Billie Holiday was not the only visiting star whom Tony accompanied – later in 1954, the Trio with Joe Harriott supported Sarah Vaughan on her concert tour, and Tony, with bassist Dave Willis, accompanied her performance with pianist Ronnel Bright, one of many concerts away from the Flamingo which Tony did that autumn, including the annual Jazz Jamboree at Kilburn’s Gaumont State and a Royal Festival Hall Modern Jazz Workshop with Tubby Hayes, Don Rendell and Ronnie Ross – all future members of Tony’s line-ups. (Image: MM Ella, Oscar story feb55) In early 1955, there was a substantial amount of publicity in Melody Maker about the appearance of the Kinsey quartet on the forthcoming Oscar Peterson/Ella Fitzgerald tour – not only would Tony and bassist Sammy Stokes accompany Oscar and Ella, but the Quartet would have their own spot, until impresario Norman Granz vetoed the proposal, making some waves with promoter Harold Fielding. Tony and Sammy did the tour anyway, however. The number of out-of-London gigs the band was doing caused Sammy Stokes to quit in March 1955, and Eric Dawson replaced him.

With Joe Harriott, the trio recorded 16 tracks over the course of a year or so, all included here. The first EP they recorded for Esquire on May 13th 1954, as was often case, featured a couple of standards along with two original tunes – in this case two by Irving Berlin and two by Bill Le Sage, one of the latter being “Last Resort” which became the band’s signature tune. The next EP, recorded on Sept. 22nd, was the first time that Bill played vibes on one of the band’s recordings.

After their next EP, done in December 1954, Tony moved from Esquire to Decca, where Tony Hall was A&R man, the move causing a six-month break between sessions. Soon after their first EP was made for Decca in May, the band was asked to record an album with fellow Decca artist Lita Roza – she was an important act for them following her No. 1 with “How Much Is That Doggie In The Window” in 1953, and Decca were happy to accommodate her desire to make a jazz-flavoured album.

Joe Harriott also moved on in the summer of 1955 to join the new Ronnie Scott Band, and Tony, at Bill Le Sage’s suggestion, brought in Ronnie Ross, former member of Don Rendell’s Sextet and then with the Tony Crombie Orchestra, who as well as baritone sax played clarinet. Tony remembers that earlier in his jazz career Ronnie was actually in the Grenadier Guards Band, and fitted his jazz work around his Army commitments until he was demobbed. Once again, the event merited a sizeable story in MM. The new line-up made its first EP in August 1955 and another in October, when they also appeared at that year’s Jazz Jamboree at the Kilburn State, of which MM’s reviewer Tony Brown wrote “This is a powerful little group. Kinsey’s solo drumming with a great variety of cross-beats was masterful.”

The publicity photo of this line-up, as indeed the previous one with Joe Harriott, exemplified one aspect of the Kinsey groups – the matching sharp suits and ties, complete with handerchiefs in the breast pocket, were part of the style of the successive groups, and although most bands of that era dressed “smart” rather than “casual”, Tony’s bands did it better than most and were the envy of many musicians. Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stonesonce legendarily observed in a radio interview that he wanted to dress like the Tony Kinsey band. Meanwhile the publicity machine was hard at work, with stories about the band possibly touring both the USA and Japan appearing more or less simultaneously – neither actually came to fruition, unfortunately.

During the summer of 1956, Kinsey decided to augment the quartet line-up with the addition of Don Rendell. Once again it attracted a headline in MM, with Rendell quoted as saying “This is a group I have always wanted to join. It is composed of good solid jazz musicians”, while Tony commented “The addition of Don will give my group a new sound and will make it more flexible.” The story on July 14th also includes the news that the group was about to embark on a 3-week tour of Army bases in Cyprus – not a bad place to spend August!

At the same time Pete Blannin took over from Eric Dawson on bass, and in October recorded a single for Decca – the Ahlert/Turk standard “Mean To Me” with a new Kinsey composition “Supper Party”. A performance of the latter also appears on a rare and previously unreleased recording from around the same time (we don’t know whether it was before or after the studio date) with three tracks from BBC’s Jazz Club with intros by the ineffable David Jacobs.

Four sessions over the next three months resulted in ten tracks which became Decca’s “Introducing Tony Kinsey” LP, released in early 1957, before Rendell and Ronnie Ross departed, the former after a relatively brief stint with the band, to form a new “mainstream” band, as MM reported. Tony welcomed back Joe Harriott on alto with Bob Efford on tenor. Tony told Melody Maker “The basic sound of the group will not alter much and will still feature originals by members of the quintet. I am pleased at having Joe back, as in my opinion, he is one of the greatest saxists in Europe. As Bob Efford has never played with a regular jazz group, this will give him a chance to develop into one of the country’s leading jazz stylists”. It’s an interesting comment on Tony’s skill and natural talent as a catalyst for groups which make them more than a sum of their parts.

The only recording with this line-up was a session for Decca in May 1957 called “The Jazz At The Flamingo Sessions”, but actually recorded in the pub next door to the Decca studios in Broadhurst via a feed from the studio (although Tony was unhappy with the fact that the drums are more or less inaudible on the recordings). It comprised six tracks, once again a mixture of standards and originals, including two from Bill Le Sage (“Pict’s Lament” and “Mystery of The Marie Celeste”) and one by Joe Harriott (“Just Goofin’”).

In the Melody Maker Readers’ Poll published in October 1957, Tony Kinsey was voted No. 1 in the Small Combo category ahead of Humphrey Lyttelton, Don Rendell, The Jazz Couriers and Chris Barber, while the NME readers voted them No. 1 in the Small Modern Jazz groups category the same month. By this time Joe Harriott had moved on once more, to be replaced by Les Condon on trumpet, bringing another fresh sound to the band, and in October ’57 they were in the studio to record “Blue Eyes” and The Midgets” for a Decca single, along with the first three tracks for a project that Decca had asked the band to do – an EP of tunes from the then current and hugely popular musical “My Fair Lady”. They recorded the remaining three titles in December, with Art Ellefson temporarily replacing the unavailable Bob Efford on tenor sax and Lennie Bush in for Pete Blannin on bass. An article in Woman’s Own magazine later in the year noted that “Tony only got ten days’ notice before recording began, so ‘My Fair Lady’ gave the band quite a headache”. The “My Fair Lady” EP was slightly odd, in that the tracks are very short, but, as Tony observes, “that was what they wanted”.

With Bob Efford back, this line-up of Tony, Les Condon, Bob Efford, and Bill Le Sage, but now with Dave Willis on bass, recorded an LP during March 1958. This was released under the title “Time Gentlemen Please” – the last under the Decca contract.

For some reason there was then a fairly lengthy hiatus between recordings – Tony can’t remember any particular reason why – the ‘live’ work was continuing with the Flamingo residency and plenty of other concerts like the annual Jazz Jamboree in late ’57, BBC’s “Jazz Saturday” broadcasts from the Royal Albert Hall in February 1958, and a TV appearance on ITV’s Jack Jackson Show alongside The Jazz Couriers (can you imagine ITV doing that these days?).

In trailing the TV appearance, one report mentions that trombonist Ken Wray had joined the Quintet replacing Bob Efford, who had joined Ted Heath – another interesting change in the instrumentation – and that the group were appearing at the Savoy in Southsea before returning to the Flamingo. Also in April 1958, the Quintet took to the road to tour with Sarah Vaughan once more, starting in Cardiff.

The next recording project took Tony down an altogether different route. Through writer Charles Fox, Tony had been introduced to Christopher Logue, long-time contributor to Private Eye, who was very much on the “alternative” side of the cultural spectrum, when he wanted some dramatic drum effects for a poetry reading on radio, which may have pioneered the whole poetry and jazz concept which became fashionable around this time. They stayed in contact and Logue came up with an expanded idea for another poetry and jazz broadcast , again for the BBC Third Programme (now Radio 3), which was done in March 1959.

George Martin, later of Beatles fame, who was then the recording manager for EMI’s Parlohpone label, and who was always interested in off-the-wall projects, heard it and decided to record it. It comprised Christopher Logue reading his translations of poems by Chilean writer Pablo Neruda from his “Veinte poemas de Amor” (Twenty Love Poems). Tony and Bill Le Sage wrote the music to accompany them. Unfortunately Christopher’s sense of timing was not brilliant, and Charles Fox had to be on hand at the recording – done completely ‘live’ with no editing or overdubbing – to prompt Logue’s cues. It’s an interesting musical aside that is very much characteristic of that era.

Tony maintained his relationship with Christopher Logue as he and Bill le Sage broadened their musical scope further, writing the music, with lyrics by Logue, for “The Lily White Boys”, a play about Teddy Boys starring Shirley Anne Field and Georgia Brown, which ran at London’s Royal Court Theatre in early 1960.

During 1959 Stuart Hamer had replaced Les Condon on trumpet, and Ken Wray had departed, the band performing as a quartet, as confirmed by a “Round The Clubs” article by Steve Race in one of the music papers in May, and once again a high profile observer noted the trademark Kinsey skills: “I have long been an admirer of Tony Kinsey, one of our leading jazz individualists. Tony in action, eyes closed, with a dawning smile on his lips, is the best example I know of a drummer who listens. No phrase played by a soloist escapes his ears; he judges with exact good taste when to echo a melodic phrase, or when merely to continue laying down that light flexible undercurrent of rhythm”.

That summer in 1959 the band played the Beaulieu Jazz Festival to around 20,000 people. The year saw another evolution in the line-up, when Stuart Hamer was replaced by the young alto sax player Alan Branscombe, who came highly recommended by Tubby Hayes, and Jack Fallon replaced Kenny Napper on bass. In October, Tony was pictured in the music press at the opening of Ronnie Scott’s Club (which proved to be a momentous occasion in the business), having a drink with Ronnie, Tubby Hayes and Duke Ellington’s trumpeter Ray Nance – maybe Alan Branscombe’s name came up in conversation!

In December 1959, this line-up recorded an EP for Parlophone called “Foursome”, the six tracks including four Kinsey or Le Sage originals. Tony may not have been making a huge number of jazz records around this time, but he was certainly busy composing and recording – a newspaper interview of September 1960 noted that Tony’s music was widely heard in jingles for TV ads, and Tony confirmed: “You can’t just make a living playing only jazz today. I must have played and helped write over 20 numbers for commercial television.” That article also noted that Tony’s band had disbanded, to which Tony replied: “We haven’t really disbanded. We are just having a temporary lay-off. After so many years without a break I think we were getting stale, but in November we go back to the Flamingo Club for a second term of residency”.

Back at the Flamingo, owner Jeff Kruger launched the Ember label of the back of an opportunist success with a Dutch single by Jan & Kjeld called “Banjo Boy”, and decided he would start releasing jazz records. He asked Tony if he would like to record an album of original material with a hand-picked line-up. Tony had never recorded with Tubby Hayes, but knew him of old, and he was an obvious choice for an all-star band. Bill le Sage was a natural choice and Jimmy Deuchar, another fellow member, like Tony and Bill, of the original John Dankworth Seven, was invited to play trumpet. Bass player Lennie Bush had been a close friend and confidant since Tony had arrived in London and was Tony’s favourite bass player, so he completed the line-up.

The album was recorded in September 1961, and released on Ember as “An Evening With Tony Kinsey Mr. Percussion”. It had its first release on CD via Acrobat in 2008. The complete album, a thoroughly classy and enjoyable piece of work, rounds off this collection, and in many ways encapsulates the Kinsey method – pulling together the best musicians of his day to produce innovative, top quality but accessible modern jazz, always underpinned by the impeccable drumming of the man himself.

The Flamingo residency finally ended when the group eventually decided to disband in 1963, not through any particular animosity between the members, but simply because Kinsey and le Sage in particular decided that eight years was quite long enough, and they wanted to do their own things.

The reputation that the Kinsey outfits established during those years has come to exemplify the essence of the leader’s approach. Writing in Jazz Journal in 1955, Keith Goodwin observed that their music was “……quiet and relaxed; stylish without resorting to exhibitionism;…….the quartet play with drive and conviction, and everything they do has the verve and spirit associated with the true jazz feeling.”

As the ‘60s progressed and the jazz scene was increasingly overshadowed by the rock and blues boom, Tony Kinsey broadened the scope of his work, experimenting with big band recordings of his own conceptualised compositions, notably the “Thames Suite” in 1974 and 1976. His career since then has revolved around composing and recording music for film and TV, including the Christopher Plummer movie “Souvenir”, interspersed with a regular round of gigs in both small group and big band formats.

In 2005, he composed and recorded a new work “Anatomy of a Jazz Festival” for a performance at the Ealing Jazz Festival, a regular annual engagement, and in 2006 composed and performed “The Embroidery Suite” to mark the opening of The Sunbury Millennium Embroidery Gallery in his home village. Since then he has composed two suites for String Quartet, both premiered in Sunbury by Patrick Halling’s celebrated ProMusica quartet, and the suite for harmonica and string quartet mentioned above. Every year for the past three years, he has performed with the Quintet to a packed house at the local Sunbury Cricket Club at the Albert Skinner Jazz Night to commemorate Sunbury’s much-loved postmaster and pillar of the community, who was a great jazz fan.

Tony Kinsey was a central character in the development of the bebop-inspired modern jazz movement in post-war Britain, and as both bandleader and drummer was (and to a considerable extent still is) at the centre of a strand of performing and recording activity that continually brought together the most talented and inventive musicians of his era.

Paul Watts 2012 (adapted from the booklet accompanying The Tony Kinsey Collection 1953-61 Boxed Set)